St. Petersburg Paradox Simulations

A friend recently posed a riddle to me:

You flip a fair coin. Tails, the game is over. Heads you win $2 and play again. In the next round, tails you take your $2 and the game is over. Heads you win an additional $4 and play again. In the next round, tails you take your $6 and the game is over. Heads you win an additional $8, and play again. And so on. The payoffs double in each round. How much would you be willing to pay to play this game?

If you are unfamiliar with this problem, it’s worthwhile to take some time to try and solve it. I needed pencil and paper [1]. When ready, scroll down to read on.

…

…

…

…

Now that you’ve had some time to think about it, take a moment to read through the solution in terms of expected value (this riddle is known as the St. Petersburg Paradox). I also enjoyed this Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy write up.

The key point is that the expected value is infinite:

So, in theory, you should be willing to pay a large amount of money to play this game (in particular, anything less than infinity). Clearly that is not a good idea - hence a paradox.

But what if you could play the game many times? By the law of large numbers, the more times you play, the closer the average of the results should be to the expected value (which in our case is infinite).

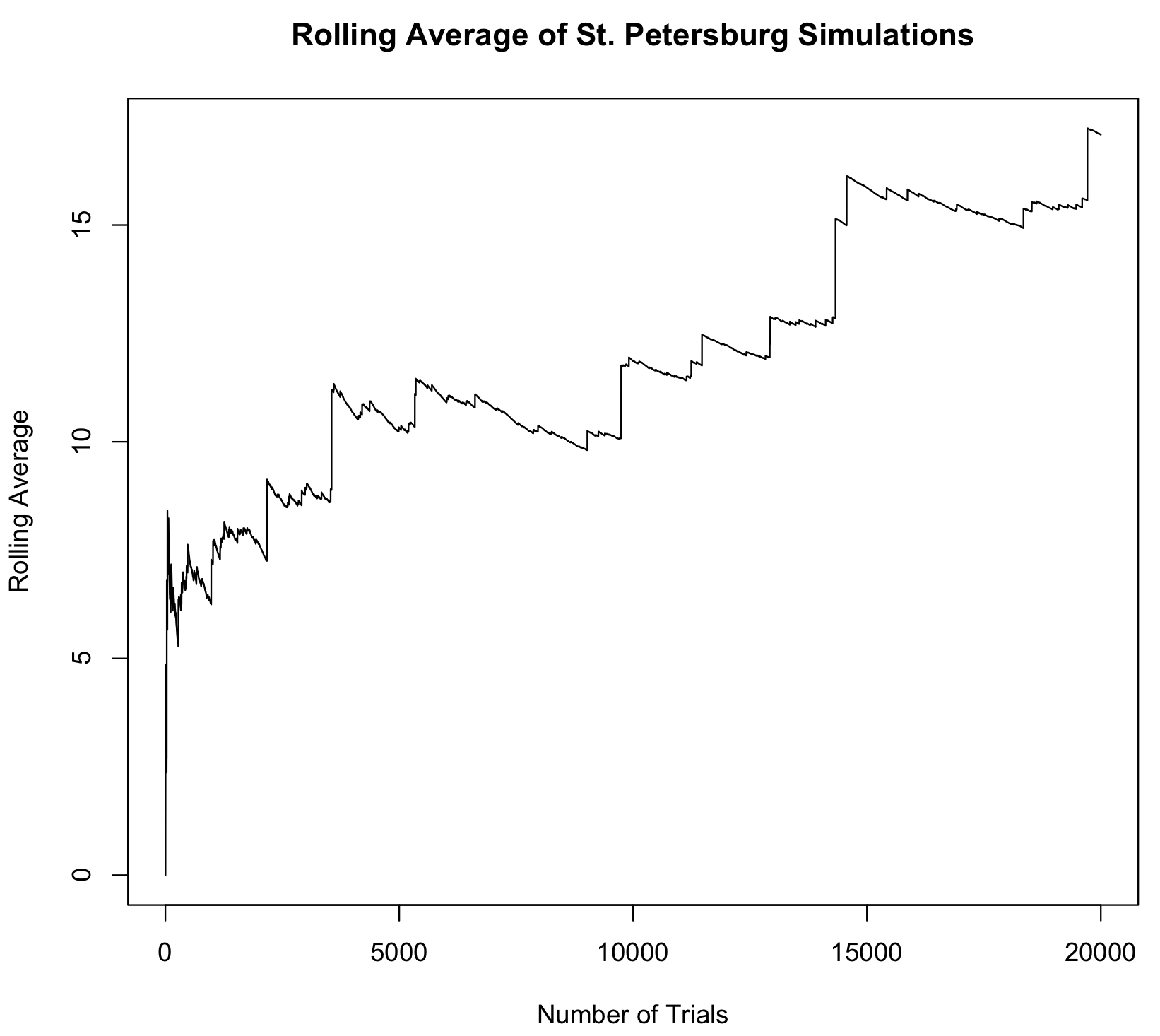

I was curious about what this would look like in reality, and wrote some R code to simulate playing the game many times. After running the code, I was initially surprised to see that even if you play the game a very large number of times, the average of the results was quite low, and quite variable. It was nowhere near approaching infinity.

The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy includes a useful graph (reproduced below) that helps explain the interesting way the simulations of the St. Petersburg approach infinity.

Essentially, every once in a while, you’ll win big. This will cause a big jump in the average of the results thus far. The average will then slowly decrease (50% of the time you’ll win 0), until another big jump. Because the average of the results increases at each jump, it becomes more difficult to increase your average as time goes on. So the big jumps become more and more rare.

I ran this for 20,000 simulations:

Full code via this GitHub Gist:

[1] I find the more I struggle with a problem - math or otherwise - before looking at solutions, the deeper my understanding of the problem. This is the idea behind the aphorism "math is not a spectator sport".

Tags: